Posts Tagged deficit

Applied Randology #3: Taxation and Misrepresentation

Posted by Cato in Applied Randology on March 15, 2012

So before we leave Part One behind, let’s add tax reform to the issues of health care, renewable energy, and the impact of lobbyists on our laws that we’ve touched on during this section of the book.

After all, Dagny spends Chapter Ten unraveling the mystery of how GM (or 20th Century Motors, as its known in the Randverse) went bankrupt, and what she discovers is that new management introduced a socialist pay scheme that basically acts as a morality play about income taxes. And here’s how:

If the Motor Company were a government, then what it did was allow tax rates to be set by simple majority rules democracy. If the hardest workers logged overtime or asked for a raise, the extra money was taxed at over 100% — for every dollar they earned, they had to pay more than a dollar back to management. Their paychecks shrunk the more they worked. The company then took the tax money they collected and gave it to the poorest workers as bonuses, so that the poorest effectively paid negative taxes.

The biggest difference between this and the U.S. tax system is not the over-the-top extremity of the rates. It’s that the Randian nightmare scenario is easier to understand than the real tax code.

The real tax code is a giant convoluted mess with an endless list of credits, deductions, and subsidies, some permanent and some scheduled to be for a limited time only. Most people are probably aware of marginal rates — your first $15,000 is taxed at 10%, the next $10,000 is taxed at 15%, etc. But those numbers don’t end up being the actual percentage of your income you pay.

In fact, that percentage can vary a lot within and between those tax brackets. Instead of your effective tax rate starting at zero if you’re poor and moving up in an arc the richer you get, the system ends up working more like a game of chutes and ladders. Thanks to all the intricacies of the tax code, if you move two spaces forward at the pre-tax level, you might find yourself moving three spaces backwards at the after-tax level. Like if you got a raise worth $500 but that put you above the limit for a $1000 tax credit, your taxes rise by more dollars than you get from the raise. The money from the raise was effectively taxed at >100%, just like it was for Rand’s hardest workers.

On the other hand, you might find that after deductions and whatnot your effective tax rate goes down and you’ve moved an extra space forward at the after-tax level. For example, if you move from the 25% bracket to the 35% bracket, every dollar you deduct saves you 35 cents in taxes, whereas the same deduction before only saved you 25 cents on the dollar. With enough deductions, your rate actually goes down when you cross into a new bracket. But the richer you get within your bracket, the more your taxes rise back up.

On the other hand, you might find that after deductions and whatnot your effective tax rate goes down and you’ve moved an extra space forward at the after-tax level. For example, if you move from the 25% bracket to the 35% bracket, every dollar you deduct saves you 35 cents in taxes, whereas the same deduction before only saved you 25 cents on the dollar. With enough deductions, your rate actually goes down when you cross into a new bracket. But the richer you get within your bracket, the more your taxes rise back up.

And if you are extremely poor, your tax credits could easily exceed your taxes owed, such that your effective tax rate is negative, and just like Rand’s poorest workers, for every dollar you make, you get money from the government. According to the Tax Policy Center, in 2010 the government effectively gave the poorest 2% of Americans an average of nearly 40 cents per dollar on their earned income.

Bartlett is one of those moderate Republicans from the '80s who is far too reasonable for today's GOP.

Obviously, these examples are a major oversimplification, and if you want more specific details I recommend reading Bruce Bartlett’s book The Benefit and the Burden. But the key point here is that unlike Rand’s nightmare scenario, in our real-life tax board game the chutes aren’t all at the top, and the ladders aren’t all at the bottom. They’re scattered unpredictably all over the place.

It’s also worth noting that this dynamic is what conservatives are talking about when they say welfare makes people not want to work. For a lot of people at the low end of the board, moving from a negative rate to a positive rate means their newly improved pre-tax income ends up being lower after-tax because of the credits they lose when they stop being so poor. They essentially get a small ladder at the start of the game, but it puts them on a space where they’d need to roll a five or a six to avoid landing on a chute and sliding backwards — any raise would have to be unrealistically large to bring the effective tax on any new money below 100%.

The error in the conservative argument is that it only calls this dynamic economically oppressive when it applies to people in the middle class or higher. According to conservative rhetoric, the poor person facing four chute spaces in a row is just a lazy moocher for taking that first tiny ladder.

If we want to reform our tax system, we could either get rid of the chutes and ladders altogether (the flat-tax conservative solution), or we could arrange them in a more recognizable pattern (the progressive-rate liberal solution). The fiscally responsible compromise would be to get rid of the ladders (close tax loopholes) and keep a few of the chutes (maintain multiple tax brackets instead of moving to a completely flat rate). But getting rid of the ladder loopholes basically means a tax hike for everybody, so no politician in their right mind would ever vote for it outside of an acute crisis.

The only actual tax changes that can make it through the normal political process are the opposite of the fiscally responsible compromise. Getting rid of the chutes is okay, because that’s cutting taxes. Adding ladders is okay, and you can even call that cutting taxes if you design the ladder as a tax credit or a deduction instead of straight spending. But just like what I described above when you try to get rid of all the ladders, even getting rid of one ladder de facto raises taxes on some class of people or other. And the more money would be freed up to reduce the deficit by removing the ladder, the more people are facing that de facto tax hike. So it’s a political no go.

If this dynamic sounds familiar, that’s because it is. It’s another step on that slippery slope towards fiscal crisis that we discussed in Hayek Anxiety and which conservatives always warn about.

But also like in Hayek Anxiety, even though politicians from both parties face these perverse incentives, today’s Republican party takes the perversity to a whole new level by campaigning on the problem (those aforementioned warnings) and governing in a way that makes it worse.

In fact in the case of tax reform, there is one specific lobbyist who wields dictatorial power over any reform proposal that crosses his desk, which is eerily similar to the villainous Wesley Mouch of the Randverse, the lobbyist-cum-bureaucrat to whom Congress grants dictatorial power over the economy.

This real-life Wesley Mouch is Grover Norquist (that’s him in the picture). He’s the leader of the Americans for Tax Reform interest group. Norquist has successfully taken over the conservative party on this issue by getting nearly all GOP congresspersons to sign a pledge to never raise taxes. The goal is to keep tax revenue low so that if congress wants to balance the budget it has to do it by cutting spending.

But that goal is different from simplifying the code, a.k.a. removing chutes and ladders from the board. And history has proved that in practice it doesn’t work — even as tax revenues drop, spending just keeps going up. Not only that, new spending is often misleadingly designed as a new tax deduction or credit, a new loophole, that can technically be called a tax cut.

Norquist is fine with adding more of these loopholes because it lowers tax revenue. But these loopholes increase inefficiency in the economy and make the deficit worse — the exact same effects that Wesley Mouch’s socialist policies cause in Atlas Shrugged and which real-life conservatives blame liberal policies for creating. For all Norquist’s success in monopolizing power over tax reform, he has completely failed to reform taxes in an economically responsible way.

If this trend is not reversed, it will eventually cause an economic crisis worse than 2008 and similar to the one that was hinted at when the GOP threatened to limit the debt ceiling last summer. But politically speaking, it is in nobody’s individual interest to address the problem until the crisis happens, because whenever somebody does the right thing on this issue they lose their next election.

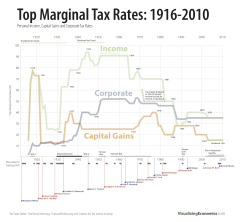

BOTTOM LINE: If the line goes higher than the top of the chart, America is truly fucked, like Greece. And literally the only way to bring the line down enough is to raise taxes and/or close loopholes.

So where does that leave us heading into Part Two? Rand’s vision of dystopian socialism does have analogues in the real America, vis a vis bizarre tax rates and potential economic collapse. But the injustice doesn’t fall so neatly along class lines, and the collapse is being brought on by today’s conservatives as much as by liberals, since the conservatives should be the libertarian, fiscally responsible party, but they have abandoned the policies and kept the rhetoric in ways that make the problems far worse.

As referenced earlier this week, Part Two is titled Either/Or, but the options Rand offers are a false choice. You can see this problem of illogic in our politics as well. The object of Applied Randology during the Either/Or chapters will be to reintroduce middle ground where Rand works hard to exclude it. If we succeed, we should be able to tie together all of the issues we’ve talked about so far into a crude vision of a progressive libertarianism that is not, in fact, a contradiction.

See you next week…